Texte paru dans le Guardian en janvier 2012

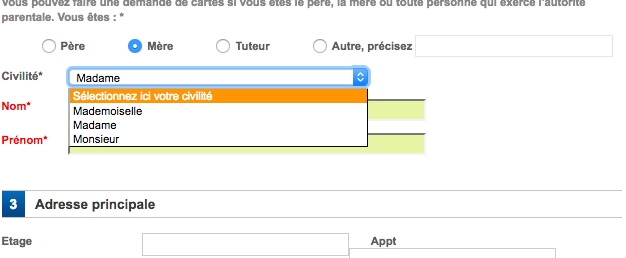

In France men are addressed as Monsieur and women as Madame or Mademoiselle. While a Monsieur is a monsieur no matter what, a Madame is a married woman and a Mademoiselle an unmarried woman. Until now all official forms have been printed with these three tick boxes, relating to what the French call civilité (a word that covers marital and civil status).

This week a circular from the prime minister instructed government offices "to avoid using any distinction of this nature … 'Madame' is to replace 'Mademoiselle' as the equivalent of 'Monsieur' for men, which gives no indication of their marital status". But I fear that yet another circular is not going to change this tenacious practice. Back in 1967 and again in 1974 a circular from the ministry of the interior stated that "Madame" should be the equivalent of "Monsieur". But things have only got worse with the internet. If you don't fill in the marital status box, you cannot submit forms, because these are "required fields". It happens with my taxes, social security and all kinds of bookings, especially for the Eurostar ... on the French form. On the English form I can tick "Ms" and no one pesters me about my private life.

A "Madame" is also of course a brothel keeper: leaving us in no doubt that "Mademoiselle" refers first of all to a sexual state: being a virgin. When I am asked to tick my civilité I am in fact being asked to give information about my sex life — single or married, available or not. It is this aspect that the two feminist groups who campaigned for the change have been protesting about.

The same intrusiveness applies to your name. When a Frenchwoman gets married, there is no legal obligation for her to take her husband's name. But most state organisations automatically change her surname. The infuriating "maiden name" box appears on the vast majority of administrative forms, payslips, invoices, medical records and even online shopping services. On my national insurance card I have found it impossible to keep my real name. As for my taxes, only in the past two years has my own name appeared next to my husband's, who remains the "head of the family" (a concept that no longer has any legal meaning, but remains in use).

A French law of 1986 makes it clear that a person is entirely at liberty to choose the name by which they are known. But a married woman is constantly reduced to her husband's name, and even to her husband's first name. So we read of the death of "Madame Robert Dupont": even in death, the woman has been eliminated entirely.

French gallantry requires a woman to be referred to as "Mademoiselle" for as long as possible, as a way of saying she doesn't look her age – and can be chatted up, or indeed fucked. Calling a woman "Madame" and correcting it to "Mademoiselle", as though you've made a blunder, is a classic chat-up line.

The freedom of women in France is very much a matter of words, and I think it is intimately related to language. As with many Latin languages, the masculine form trumps everything when it comes to grammatical agreement of adjectives and so forth. We say Un Français et trente millions de Françaises sont contents; those 30 million French women have to be contents in the masculine form as dictated by their one male companion, rather than contentes as they would be without him.

A lot of men tell us that we are fighting the wrong battle, that we should fight first for wage equality, or against the glass ceiling. But words matter. Let's imagine unmarried men having to tick the box Mon Damoiseau, the medieval equivalent of Ma Demoiselle. The boys soon stopped allowing people to call them bird, with its insinuation of virginity. Whereas I, at the age of 43, still get called "Mademoiselle", literally "my little hen". Charmant, non?

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/feb/24/madame-mademoiselle-sex-french-women