Written two months after the attack against Charlie Hebdo. Paru en français dans Libération, puis en anglais dans Artreview.

After two months, words. And death everywhere. In this moment the intellectuals who seem incapable of mastering their death drive are identifying with the murderers. A drive deep within us all, a desire we have to shoot real bullets, but which doesn’t urge us to find excuses for murderers.

For example, on the web site of the New Yorker, an article by Teju Cole, or Will Self on the Vice web site. Two different authors, both representative of the “I’m Not Charlie” spirit. Their overarching argument is that murders happen elsewhere, all the time. As if the fact that murders happened elsewhere diminished in the least the murderers of this world. The death drive still incurs death en masse, not like the end of a single life.

This anti-Charlie pose may seem chic and original, but it is based on a truly banal fascination with destruction. Destroy, they all say, believing themselves the only ones to say it. In these arguments fixated on violence, the victims are guilty of their own murder, like a raped girl might be guilty because she attracted attention. The real murderer is erased, he becomes invisible, unimagined, a blind spot in our unconscious: we will no longer be able to see him, because he is within us. And these are the victims we accuse, with a reversal these authors defend with a “slightly” and a “however.”

Teju Cole is part of the brilliant diaspora of young Nigerian writers. He has one foot in New York and the other in Lagos; he’s a writer of cities and of the world, but the Parisian context escapes him. Oh, he’s very sorry for the victims. But for him Charlie is a racist newspaper. And so he doesn’t want to realize that a drawing by Charb showing Christiane Taubira, the French minister of justice, as a monkey is a denunciation on the racist attack by Minute. Indeed, Taubira attacked Minute in the courts, and not Charlie. But the Internet is filled with false reproductions of this drawing missing the flame of the Front National that Charb included, and shorn of its denunciatory title RASSEMBLEMENT BLEU RACISTE [RACIST BLUE ASSEMBLY]. A truncated and false quotation, which amounts to a transgression. Will Self, on the other hand, the prolific English author, explains that in any case France is a bloody country of terror (Sade, the French Revolution). His hasty version of the Enlightenment is a comical dismantling of French culture—until he denounces the “terroristic brush” of Charlie Hebdo. A disgusting and distorted metaphor, even in a musical sense. Not an accurate one.

I can see exactly what these writers are doing: they are no more journalists than I am. Journalists have an obligation to the truth, to some modicum of fact checking. But writers are artists. They certainly have a writer’s point of view. They’re allowed to make approximations. Exaggerations. They tell themselves that “it’s all right,” because their style, yes, their images, will take care of everything. Their style supplants reason.

But just writing isn’t enough; one must, as Godard said, write justly. For writing to be action and not just words. For it to happen in the right place and at the right moment. In my case, now, this also means writing for Charlie Hebdo. And doing so repeatedly, together, to keep alive a newspaper that is free of religion, free of racism, and free of violence.

What is a just image? It might be a fiction. Such as a fiction by Walter Benjamin. One found in his On the Concept of History (1940). There, Benjamin talks about the July Revolution:

“During the evening of the first skirmishes, it turned out that the clock-towers were shot at independently and simultaneously in several places in Paris. An eyewitness who may have owed his inspiration to the rhyme wrote at that moment:

Who would've thought! As though angered by time’s way

The new Joshuas beneath each tower, they say

Fired at the dials to stop the day.”

I haven’t been able to verify the fact that there were insurgents in July, 1830, to shoot at the clock-towers and stop time. Conventional time, that of gears and sprockets. Throwing time on the streets. Firing at minutes for the revolution. Choosing other coordinates. No, I wasn’t able to fact-check that image. But you can hear it, its truth. The insurrection is there, before our eyes, and Benjamin isn’t wrong, he recreates the image, he broadcasts it, it proliferates, it lives. The image is perhaps too beautiful to be true, but it is true in its beauty.

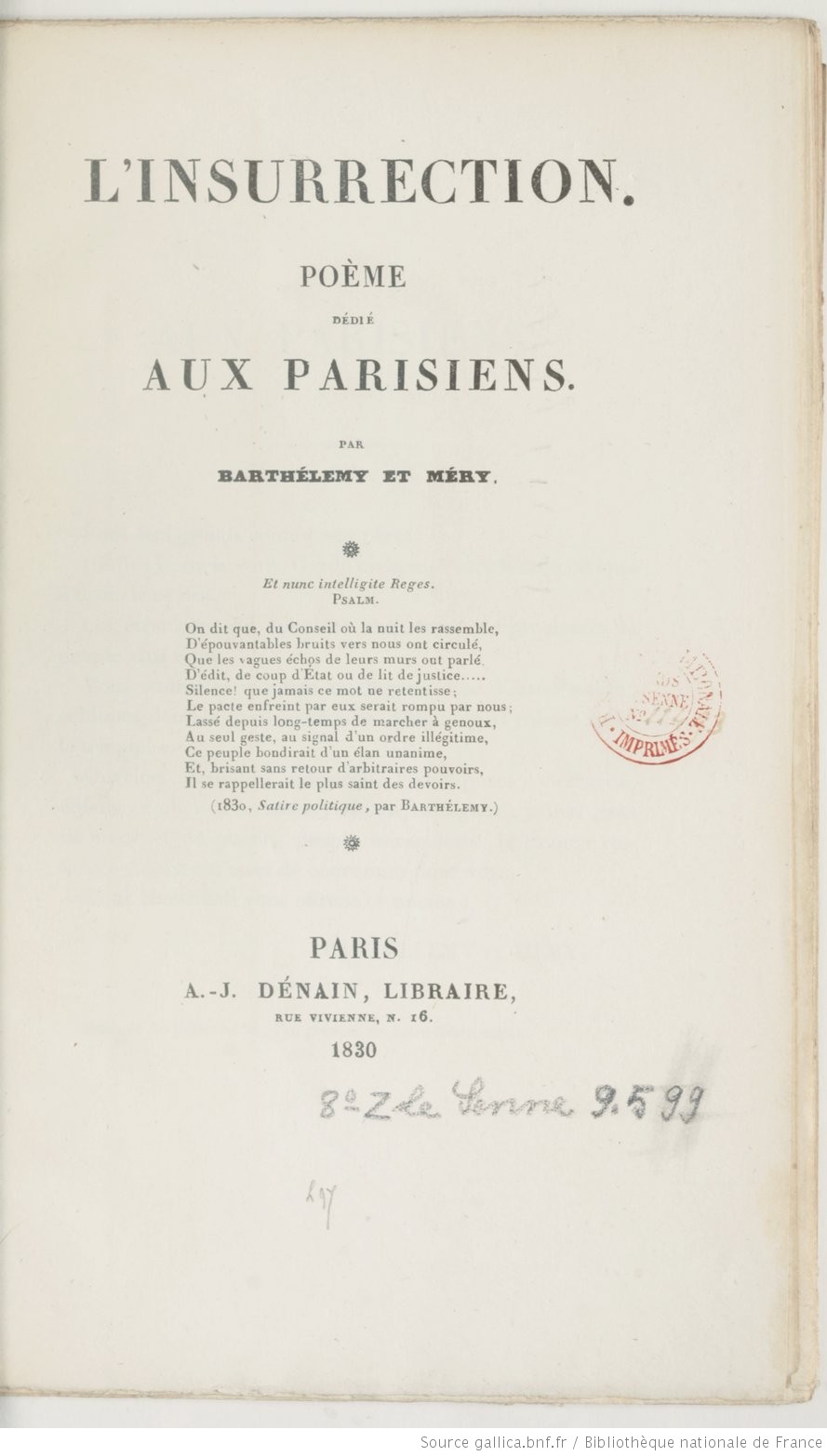

I am looking for its origins on the Internet. The poem is titled “L’Insurrection. Poème dédié aux Parisiens.” I learn that there are two authors and that they were inseparable: Auguste Marseille Barthélémy, and Joseph Méry. They talk about bloodshed. And they continue their poem:

“ Paris! What tint anguished

Its roofs blend with the sky’s shadows.

Its sad people silently meander alleys,

Contemplating the great city extinguished”

January 2015, the Eiffel Tower extinguished. A minute of silence. Everything reverberates. Literature as an antidote to stupidity.